Just 732 teenagers scored a clean sweep of 9s this summer, with more girls scoring straight top grades than boys.

Overall GCSE pass rates rose this year in the wake of the biggest shake-up of the exams for a generation.

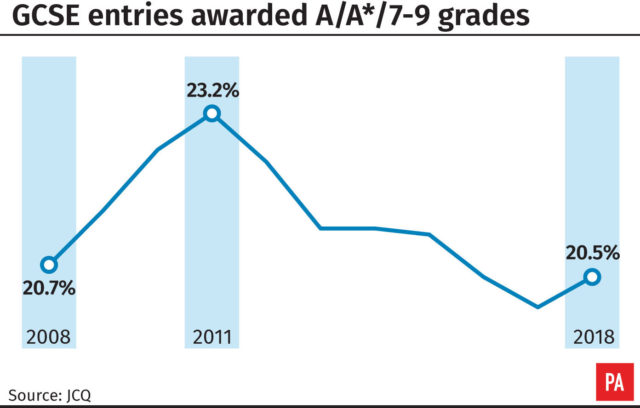

One in five UK GCSE entries (20.5%) scored at least an A grade – or 7 under the new grading system, up 0.5 percentage points on last year, according to data published by the Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ).

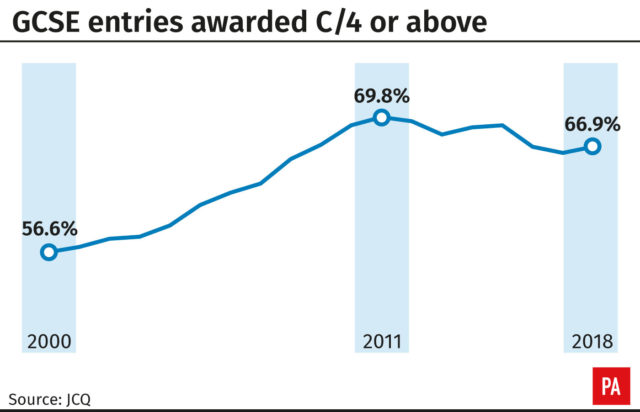

And about two thirds (66.9%) were awarded a C, or a 4, also up 0.5 percentage points compared with 2017.

Figures published by the exams regulator Ofqual showed that 732 16-year-olds in England taking at least seven new GCSEs scored grade 9s in all subjects.

Of these, almost two thirds (62%) were girls, and just over a third (38%) were boys.

One estimate ahead of results day suggested that as few as 200 candidates would score the highest grade across the board.

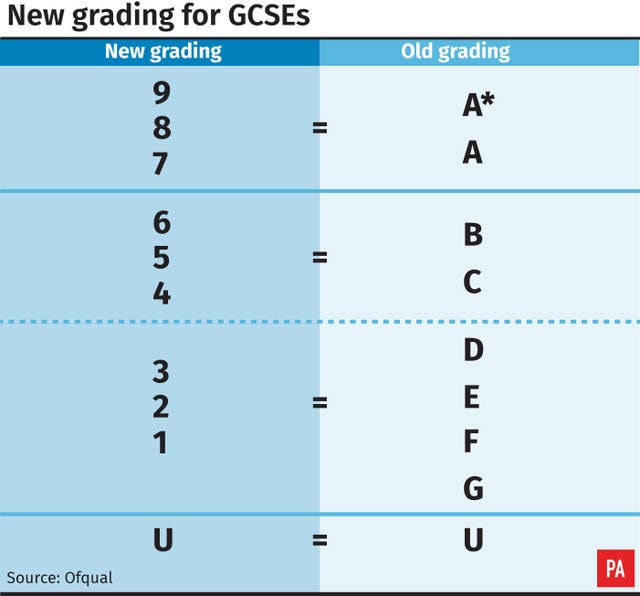

The rises in overall pass rates come after major reforms in England designed to toughen up the qualifications and the introduction of a new 9-1 grading system, replacing A*-G grades.

A new grade 7 is broadly equivalent to an A and a grade 4 broadly equivalent to a C.

There is also less coursework in new GCSEs and students take exams at the end of the two-year courses rather than throughout.

The vast majority of entries in England were for the new-style GCSEs this year, with 20 subjects, including the sciences, popular foreign languages, history and geography moving over to the new system.

They join English and maths, which were awarded numerical grades for the first time last summer.

A smaller proportion of entries were awarded a grade 9 this summer – the new highest grade, compared with A* under the old system.

This follows a deliberate move to allow more differentiation among the brightest candidates.

There are now three top grades – 7, 8 and 9, compared with two – A and A*, previously.

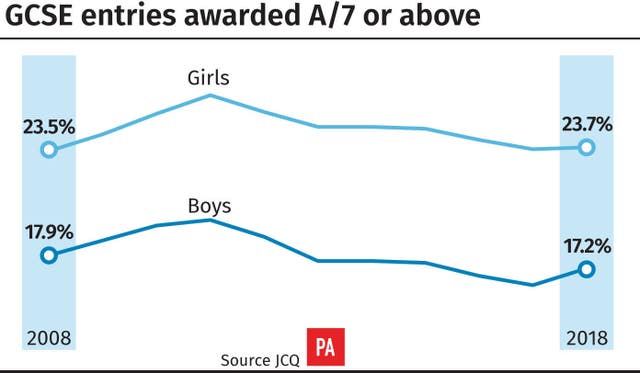

Overall, 4.3% of all UK entries were awarded a grade 9, and a breakdown shows that 5% of girls’ entries scored the highest grade compared with 3.6% of boys’ entries.

Figures for England alone also show a rise in results.

In total, 20.3% of all entries from English candidates (for both new and old-style GCSEs) scored at least an A or a 7, up from 19.8% last year.

And 66.6% scored at least a C or 4, up from 66.1% in 2017.

An analysis of grade boundaries for the new GCSEs shows that candidates taking higher-tier maths needed to get between 20%-21% of marks in order to get a grade 4, compared with around 18% last year.

Exams regulator Ofqual has said it uses statistical processes to ensure that results are comparable year-on-year, and to ensure that students who are the first to take the new-style qualifications are not disadvantaged in any way.

Professor Alan Smithers, director of the Centre for Education and Employment Research at the University of Buckingham, said: “There has been a lot of anxiety about the exams and some confusion about the new 9-1 grades, but in fact the grade level is much the same as it was.

“The percentages getting 7 and above and 4 and above are up a bit this year, which is against the trend of recent years.

“So Ofqual may have over-compensated for the fact that the people taking these exams are the first to do so and could have been disadvantaged.”

He added: “It looks very much as though the awarding of grades has been a lot more lenient.

“If the exams are generally tougher, the awarding of the grades has had to be more lenient.”

Thursday’s results also show that across the UK boys are closing the gap with girls at top grades – 17.2% of boys’ entries scored an A or a 7, up from 16.4% last year, while girls’ remained static at 23.7%.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), said: “All the time and effort that has gone into reforming GCSEs, why have we done that?

“Because GCSEs were designed for an age when children were then maybe going into employment or going into the sixth form, so they were a gateway to other things.

“Now everyone has to stay in education to 18, so why have we got children doing at least 30 hours of exams, all the stress and all the time and all the money that is, when actually for employers, it’s what they get at

the age of 18 that’s going to be important.

“That’s where the real reform should be happening. And this is looking to me like a qualification that time forgot.”

He added that there should be more focus on the youngsters who score at the lower end of the grade scale.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel