As the battle for the future of Queen Mary's Hospital, Sidcup, continues, an exhibition has just opened which will remind people of its hidden past.

MENTION cosmetic surgery today and people automatically think of tummy tucks, boob jobs and liposuction.

But a new exhibition which has just opened at the National Army Museum, Royal Hospital Road, Chelsea, puts the whole concept into perspective.

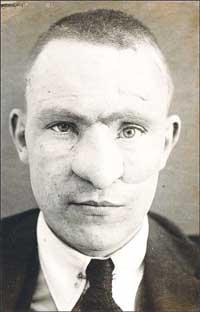

Faces of Battle tells the story of the men who returned from the trenches of the First World War with terrible, disfiguring facial injuries.

Although the trenches, dug for the soldiers' protection, shielded their bodies from much of what the enemy could fire at them, their heads were exposed to sniper fire, shrapnel and artillery raining down on them.

Among them in France in 1915 was a surgeon, Harold Gillies, who realised the scale of the facial injuries soldiers were suffering.

He successfully argued for a special ward and ultimately a whole hospital - Queen Mary's, then known as Queen's Hospital - where the badly disfigured men could undergo pioneering treatment to try and rebuild their faces.

As the Battle of the Somme began in 1916, Gillies prepared to treat up to 200 injured soldiers. Two thousand arrived.

At this time, most field surgeons simply stitched the edges of facial wounds together to stop infection, leaving men's faces to become twisted and horribly disfigured as the scar tissue tightened.

Many were terrified of seeing their wives and families again because of the terrible state of their faces.

But Gillies pioneered new treatments, using bone and cartilage, to reconstruct the damaged faces, and a method of growing "tubes" of the patient's own skin to be used in grafts to help repair injuries.

Often they faced years of hospital treatment at Queen Mary's, where Gillies worked.

The co-curator of the exhibition, Samantha Doty, says Britain was prepared to glorify its dead and welcome home its heroes, but found it difficult to cope with the badly wounded who returned.

She said: "In Sidcup, street benches were painted a different colour to warn locals disfigured hospital patients might sit there."

She added: "The impact of Gillies' work cannot be underestimated."

The exhibition features photographs and film footage from Queen Mary's own archives, which is the largest archive of medical material from the First World War in the world.

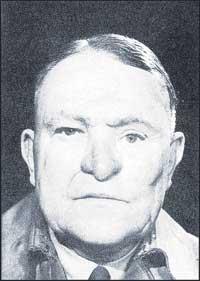

When its curator, consultant rheumatologist Dr Andrew Bamji, took over the job in 1988, the archive consisted of little more than a couple of files of pictures.

Now it comprises an entire library of medical notes, photographs, diagrams and artifacts, which Dr Bamji is still adding to, often using the internet to track down and obtain items.

This is the first time the material has featured in a major exhibition, because of the disturbing photographs, although it is available to view at the hospital.

Dr Bamji also gives lectures on the subject.

He said: "Many people think facial reconstruction began in the Second World War at East Grinstead, and we can at last set the record straight."

In fact, the more famous Dr Archibald McIndoe, who treated burned airmen from the Second World War, trained under Gillies.

Dr Bamji says the exhibition is a reminder many of those who survived lived for decades with physical and mental problems.

He added: "It places Queen Mary's in its rightful position as the source of modern facial surgery techniques through the work of Harold Gillies and his fellow surgeons, anaesthetists, radiologists, dentists, technicians and artists, here in Sidcup."

"I hope many will be able to visit the exhibition, which displays our treasures in a way we could never do here at Queen Mary's."

It also features a series of textile sculptures by artists Paddy Hartley, inspired by the story of Gillies.

The exhibition is free and will run at the museum for the next six months. It is open daily from 10am to 5.30pm.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article