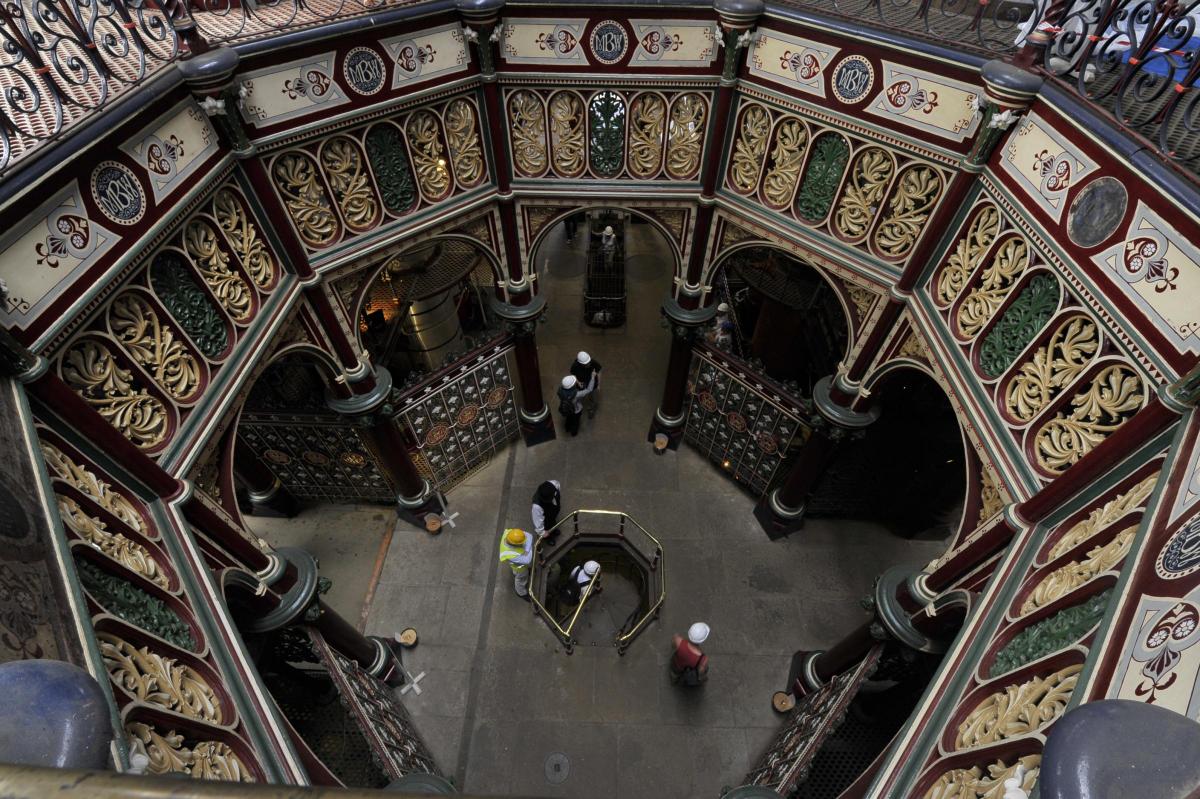

At a little-known site in the top corner of Abbey Wood, there’s a hidden cathedral of sanitation – an architectural gem and a civil engineering marvel.

The Crossness Pumping Station, built by Sir Joseph Bazalgette in 1865 to combat London’s ‘Great Stink’ and a cholera epidemic, has reopened following an extensive restoration.

The Heritage Lottery Fund has ploughed £2,774,000 into the project since the Crossness Engines Trust was founded to restore the site in 1988.

Billed as a ‘Victorian cathedral of ironwork’, the site houses four massive rotative beam engines, including the largest working example in the world.

Mike Jones, Treasurer of the Trust, stumbled across an open day at the site 20 years ago and was immediately in awe of the intricate architecture and powerful engines.

As one of a small group of volunteers dedicated to the site’s regeneration, he told News Shopper: “During the 19th century there was a very significant increase in London’s population, just around the time that flushing toilets came into fashion.

“Cess pits were overflowing and the tributaries of the Thames became an open sewer.

“By 1858 the Great Stink was in full swing, and the pollution was so bad that Parliament was on the verge of moving out of the House of Commons.”

The year after Crossness was built, there was only one instance of cholera, Mr Jones says – and official records show the last indigenous case of cholera in England and Wales was reported in 1893.

Mr Jones added: “Bazalgette really brought forward a solution that saved the lives of tens of thousands of people.

“It’s still the backbone of the London sewage system today.”

MORE TOP STORIES

And appropriately enough, Crossness stands side-by-side with Thames Water’s current sewage treatment plant.

As part of the new exhibition, visitors can walk through a replica sewer tunnel, learn about the history of sanitation in the capital and see the 250-tonne engines in action.

And the might of the massive engines, each of which are around 80ft high and 80ft wide and weight around 250 tonnes, is matched by the grandiose design of the ironwork itself.

So impressive and groundbreaking was Sir Joseph Bazalgette’s masterpiece that the engines were named after members of the royal family – as a compliment.

So the namesakes of Victoria, Albert Edward and Alexandra loom over visitors in all their waste-processing glory.

Mr Jones said: “When you bear in mind that these engines are there to pump sewage…well, it wasn’t an insult at the time.

“It was linking the royal family to a great feat of British engineering.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel